Ulnar Neuritis (Cubital tunnel syndrome)

What is it?

One of the nerves that supplies the hand is called the ‘ulnar nerve’. Like a telephone cable, it passes through a protective conduit (a tunnel) behind the inner bony prominence of the elbow. This bony prominence is called the ‘medial epicondyle’ (the ‘funny bone’). The other bony prominence is the tip of the elbow. The tunnel is between these bony prominences and is called the ‘cubital tunnel’. The roof of the tunnel is formed by a band that attaches to these bony prominences (‘Osbourne’s ligament’). The nerve can get compressed in this tunnel and cause symptoms. The condition is known as a ‘Cubital Tunnel Syndrome’.

What is the cause?

This is the second most common cause of nerve entrapment. In the majority of patients, we do not know what causes this syndrome. Mechanically the nerve gets stretched every time we bend the elbow and it pushes against the medial epicondyle. With time this causes irritation and compression of the nerve. It usually occurs in middle age. The condition is associated with diabetes, previous elbow injuries/fractures, arthritis & rheumatoid disease.

What are the symptoms and how is the condition diagnosed?

The main symptom is tingling or pins and needles in the hand. The symptoms usually affect the little finger and ring fingers. This is because the ulnar nerve supplies sensations to these fingers. Tingling is often worse at night or first thing in the morning. This is because most people sleep with their elbows bent or with their arms above their head.

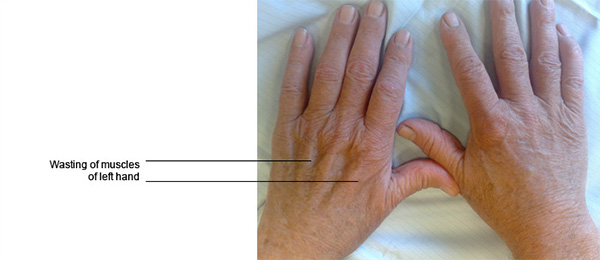

In the early stages, the symptoms are intermittent but later become continuous as the condition worsens. Patients may initially complain of pain on the inner aspect of the elbow and will notice numbness in the fingers. Later symptoms of weakness and wasting of the muscles of the hand may develop. The most commonly wasted muscle mass is in the first web space, on the back of the hand between the thumb and the index finger. Patients may drop objects and feel clumsy with their hand(s).

The diagnosis is further confirmed by various clinical tests that assess the strengths of various muscles supplied by the median nerve.

Will further tests or investigations be needed?

The diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome is made clinically but you will nearly always be referred for electrical tests (nerve conduction studies). The tests may be to confirm the diagnosis in patients in whom the symptoms and signs are not typical, and also to confirm that the nerve is not compressed elsewhere (usually in the neck from where it begins or rarely on the front of the wrist).

What is the treatment?

- Splints: They keep the elbow from bending and may be useful if worn at night. Instead of an expensive splint you could wrap a towel round the elbow and hold it in place with a tape (like a pig in a blanket). Avoid activities that keep the elbow bent for a long time. Keep more space between your work and your chest when working at the desk to keep the elbows more straight.

- Surgery: The primary aim of surgery is to prevent deterioration by creating more space for the nerve and to reduce pressure on the nerve. There are several methods described but the choice of the operation depends on the surgeon’s experience and anatomy of the ulnar nerve and the elbow.

Decompression of the ulnar nerve: This is the standard operation advised and is an open surgical release of the cubital tunnel. A skin incision of 5 cm is required and at surgery the roof of the cubital tunnel is opened, thereby decompressing the ulnar nerve. The procedure can be carried out under local or general anaesthesia, as a day case. At surgery a tourniquet cuff is applied around the arm so as to stop bleeding and make the operation safer and quicker. This tourniquet is needed for about 15 minutes and can be uncomfortable when the operation is carried out under local anaesthesia. After the operation, a sticky dressing is applied over the surgical wound. A bulky supportive cotton-wool dressing then goes on top of that. This supportive dressing is reduced after a couple of days. The small sticky dressing should be left for 10 -12 days when the stitches will need to come out. The arm should be kept elevated after surgery for 1-2 days as this will prevent the fingers from swelling and causing discomfort. Light use of the limb should be possible immediately after the day of surgery. Active movements of the fingers/ wrist/ shoulder are recommended soon after surgery.

Endoscopic decompression of the cubital tunnel Some surgeons advise endoscopic decompression of the cubital tunnel (key hole surgery). A telescope is used and surgery is visualised on a television monitor. A smaller incision is needed and an earlier return to work is possible. The risks associated with the procedure are greater. It is debatable as to whether the benefits of this procedure significantly outweigh the risks.

Ulnar nerve transposition: This is another common type of surgery where the ulnar nerve is moved from behind the funny bone, to beneath the muscle on the front of the funny bone. This way, the nerve will not stretch when the elbow is bent. In about 7-10% of patients the ulnar nerve can flip to the front of the elbow by itself (subluxing nerve) and this operation will be considered. Similarly this is the operation of choice for patients with an elbow deformity.

Medial epicondylectomy: This operation is sometimes advised, though less commonly in this UK. Here, the funny bone is removed allowing the nerve to move freely as the patient bends the elbow.

- When certain other conditions (like rheumatoid) arthritis are present, clearing of the soft tissue lining (synovectomy) or excision of any bony spurs, may be needed.

What happens if it is not treated?

Some mild cases of cubital tunnel syndrome may recover spontaneously. If the condition is neglected most people will find that symptoms become progressively worse. The ulnar nerve will continue to be compressed, resulting in total, constant numbness, due to wasting and weakness of the muscles supplied by the nerve in the hand. This will lead to permanent, irreversible muscle weakness, affecting functionality.

What is the success of surgical treatment?

The operation has a very good success rate in the early stages. It results in good resolution of night pain and tingling within a few days. However if the condition has been present for a long time, then recovery from symptoms of constant numbness and muscle weakness is unpredictable. However one of the aims and benefits of surgery is to stop the nerve from deteriorating due to constant compression. Thus even if the procedure does not reverse the symptoms, it will help to prevent progressive worsening of the nerve function.

What are the complications of surgical treatment?

The surgical scar may appear reddish for 2-3 weeks and may be tender for 6-8 weeks. However it is seldom troublesome in the longer term. An area of numbness may persist around the scar.

Infection of the wound is possible and in the early stages can be successfully treated with antibiotics. If pain increases after surgery infection needs to be ruled out.

Stiffness of the upper limb joints is possible and hence the need to exercise the limb soon after surgery. Severe complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a rare but serious complication after upper limb surgery. Unfortunately it is not possible to predict this problem but needs to be watched and treated (usually with just physiotherapy) if it develops.

Damage to the ulnar nerve is possible but very rare when the open surgical technique is used. The risk is higher when the endoscopic technique is used.

Any surgical intervention has the risk of developing unpredicted complications or setbacks. These complications may have the potential to leave the patient worse than before surgery.

Is there anything I can do to improve outcome?

- After surgery keep the hand up to help reduce swelling.

- It is advised against wearing rings on the operated hand for 4-6 weeks following surgery.

- Start exercising your limb immediately after surgery (make a fist, and then stretch your fingers out; bend your wrist forwards and backwards and touch each finger tip in turn with your thumb). This will help avoid finger swelling and stiffness.

- Keep the wound dry.

- Once the stitches have come out the scar can be massaged regularly with a soft non-perfumed cream for a couple of months.

- If the scar is tender to press, tapping along the scar and on either side of it firmly with your fingertips a few times a day may be useful.

When can I do various activities?

Return to work depends on many factors including the nature of the job and hand dominance.

- Generally patients can return to a desk job within a few days and perform reasonable tasks with the hand.

- Avoid pressing heavily on the scar.

- Manual work should be avoided for 4-6 weeks.

- Driving should be possible within a week of the operation.

MENU

MENU